This Kikongo idiom “When something else is going on,” best expresses the subject of this section, the suspicion that sickness or other misfortune is caused by the feared effects of anger, a simmering feud between lineages or families, jealousy and back-biting in the kin group—for all of which specialized treatment is required. A digest from a chart in Janzen's Quest for Therapy in Lower Zaire details various "journeys" seeking to deal with this "something else." "Witchcraft" and "sorcery"— perjorative English words that have been used mostly by outsiders since the colonial era to describe this realm of concern—do not begin to convey the varied ways that African medicine is pressed into service to deal with emotionally charged and conflicting situations. In Africa, medicine involves not just an understanding of the inherent qualities of materials, but also the nature and power of the universe, the intended effect of the application of healing materials and the way these are affected by relationships between people, and between the living and the world of ancestors and spirits. A course of healing may involve a hierarchy of resort from simple to complex, from matter-of-fact to social causation and techniques to achieve resolution of tensions and related physical problems. The goal of this section is to lead the visitor, who will have just come from the section on divination, through the labyrinth of ways that sicknesses are dealt with “when something else is going on.”

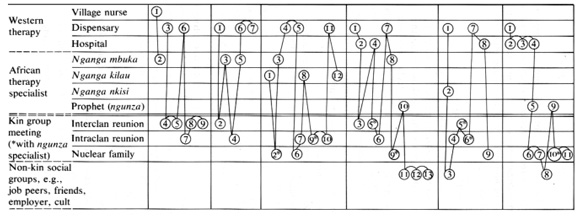

Graphic from a chart in Janzen's Quest for Therapy in Lower Zaire details various "journeys" seeking to deal with this "something else"

Medicine as Protective Charm and Aggressive Defense is one approach widely used to the uncertainty of "something else going on." A medicated figure of the Southern Savanna Songye people collected in 1906 is the self portrait of a man who is trying to protect his family—represented by hair from heads of each member as part of the “medicine” attached to the figure. A Kongo statue from the Loango coast in white chalk shows a similar measure for protection. From the Sherbro of coastal Sierra Leone come well-preserved plant substances to protect a garden from theft along with a recipe for an antidote should an individual trespass and be stricken by a headache caused by this medicine. More ominous is the anthropomorphic carved cup from the Awongo of the Kasai-Kwilu border area along the Loange river in Congo that is reported to have been used to administer the poison ordeal to someone suspected of having caused another person's death or sickness.

Healing as Reconciliation

A further subsection is called Healing as Reconciliation. Healing may also be sought through reconciliation of groups in a conflict suspected to be causing sickness, or public order may itself be buttressed through community medicine or appeal to a spiritual foundation of strength. A photo shows a reconciliation gathering of two Kongo lineages that have been at odds for a long time, but took the sickness of one of their prominent members as a justification to end the feud. A medicine mask from Liberia demonstrates how medicine may create or strengthen community authority in order to protect and enhance well-being.

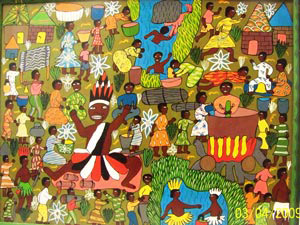

Embracing the Affliction: Responding to Spirit Calling presents a further approach to handling the sickness believed caused by "something else going on" –aggression, pollution, ill-will, deformity, variously afflicted etc. Under the tutelage of a healer, the afflicted organize as a socially-sanctioned support network comparable to a Western self-help group or twelve-step program. “Embracing the affliction" as a mode of healing is commonly accompanied by the attribution of the condition to a spirit or ancestor who has possessed the individual(s) and seeks recognition and placation. Initiations, long-term therapies, and rituals of purification and counseling characterize these therapies. Many conditions that are regarded as chronic are accepted as the will of ancestors or spirits. Family and diviners urge sufferers to embrace the affliction, join a support network of the afflicted, and perhaps become a healer. Such specialists are frequently referred to as "suffering healers," “chosen” by the ancestors or spirits whose identity is transformed by the “drum of affliction" and whose song-dance is the calling voice.

Four photographs of ngoma in Capetown, South Africa, will show novices wearing white clothing and anointed in white chalk to demonstrate their liminal status of being in close association with the spirit world, in contrast to colorfully dressed fully-qualified healers of the ngoma network. These outward embodied representations—animal skins, costumes, beads, caolin—demonstrate the individual’s transformation as he or she overcomes or stabilizes the spirit-called affliction and becomes a healer. Two furs are exhibited from sangoma apparel in Capetown. From Bulawayo, Zimbabwe comes an ngoma drum used by a spirit medium, and a painting about Becoming a N'anga by a Bulawayo artist. The painting shows the sickness-vision quest with the water spirits under the water, and the preparations for the final celebration of the sufferer-novice turned healer. Videofilms of the Capetown and the Bulawayo ngoma setting will be shown in this section.

Chronic Sickness and Spiritual Calling as Identity presents insignia of two healing orders: bracelets of members of the historic Lemba order of Lower Congo that emerged with the coastal trade to reconcile the contradictions that traders had to deal with, and a necklace from the Zar cult of NE Africa.

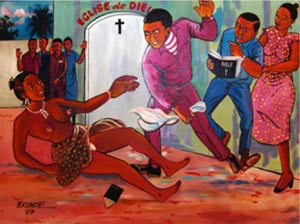

Exorcism as Response to Spirit Calling presents an alternative to embracing the affliction that is promoted in mission churches and evangelistic Christian churches in the 21st century, namely the exorcism of the spirit as an evil spirit. This subsection shows the painting Eglise de Dieu (Church of God) in which a Christian cleric in fine suit exorcises a possessing spirit from a young woman.

This section may well be the most difficult of the entire exhibition for an average Western visitor to comprehend. To address this challenge, stories of particular cases of individuals will occur throughout the section—as elsewhere in the exhibition. Questions will be raised that offer visitors a bridge of understanding from their experiences to those depicted in the exhibition. How do we deal with chronic affliction? The ways that the disabled or specially-gifted are organized? How do we handle the lingering memories and feelings of past strained relationships? Of persons who died, were killed, disappeared, without proper burial and commemoration? How do we deal with situations where conflict is believed to affect the health of individuals? Does African medicine have insights that Westerners can learn about with benefit, especially since the features covered in this section and their therapists continue in strength even after the establishment of modern biomedicine.